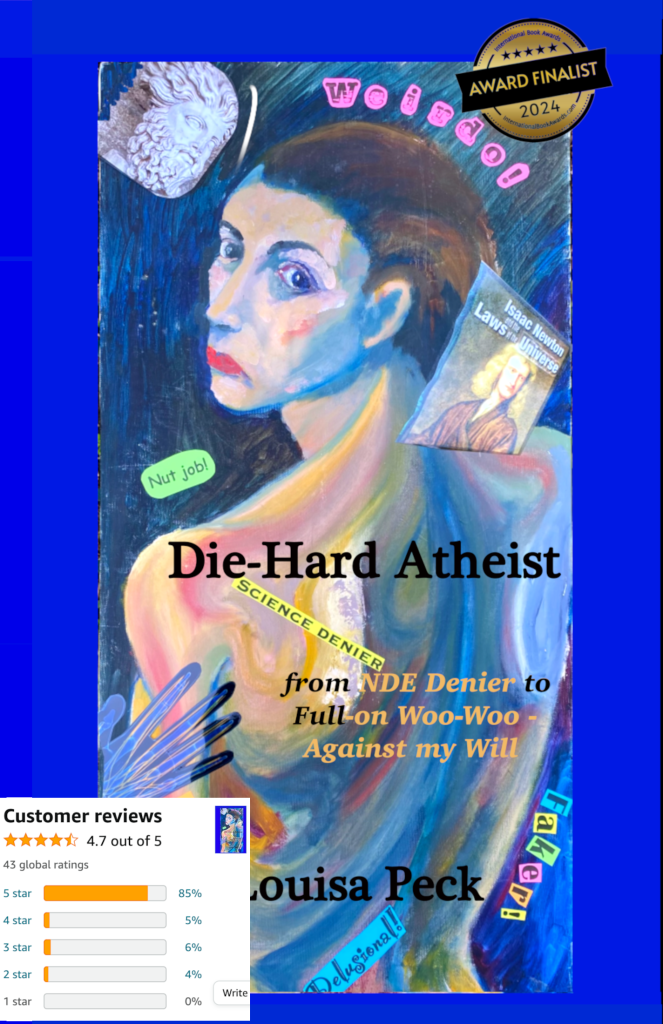

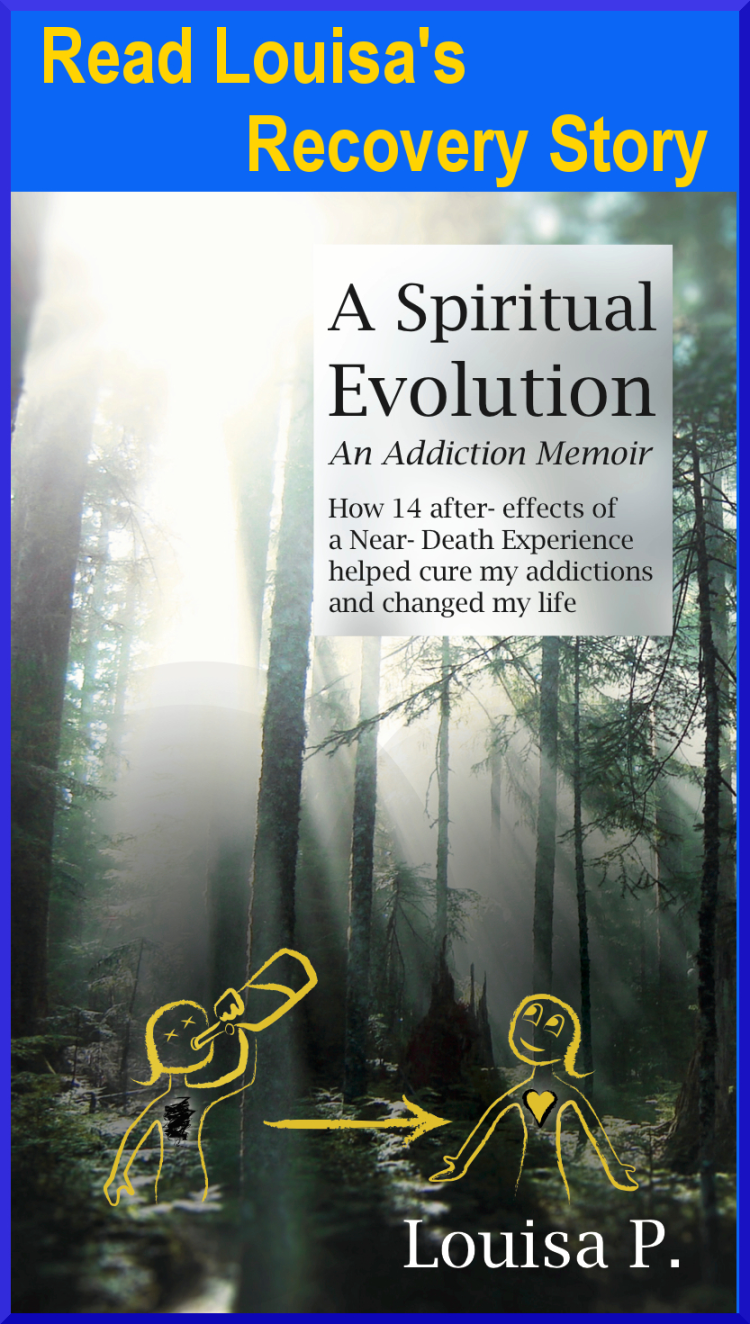

Yes, this blog’s main topic is recovery from alcoholism — BUT it’s based in my own recovery, which has a lot to do with my 1982 Near Death Experience and the many paranormal aftereffects it brought on. My spirituality is all about these ongoing encounters with the spirit world. I’m currently writing a book about them titled Die-Hard Atheist (as opposed to my addiction memoir, which is 90% alcoholism/love addiction and 10% NDE-related).

Describing paranormal experiences that contradict the mainstays of mainstream science is hard. You become vulnerable. Most people who haven’t had such experiences assume you’re either a) making stuff up for attention or b) so dumb you mistake normal variations of mind for metaphysical stuff. But here goes.

In November 2019 I communicated with my father, who died in 2008.

Since my NDE, I’ve accidentally read people’s minds on many occasions, in addition to foreknowing events and hearing from my guardian angel on the regular. In the fall of 2019, I attended a conference of the International Association of Near Death Studies (IANDS), where I described these experiences to a fellow NDEr with powers of mediumship. I’ll never forget the moment she smiled at me and said, “You’re a medium, honey! You just haven’t developed it.”

The communication with my father took place at our family summer cabin — a place he dearly loved. The cabin is rustic and constantly trying to go back to the earth, so my dad used to always keep busy with maintenance and fixes, saving money with DIY repairs. That’s exactly what I was doing — replacing the mossy, rotted shingle roof on the toolshed after a falling tree branch had crushed a corner of it.

All day Saturday I worked up there in the pouring rain,  shielding with tarps whatever needed to stay dry. I kept feeling my father’s presence in a way I often do when I’m fixing stuff around there. He seems to be witnessing my work, approving. Over the course of the day, I was steeped in this feeling of his presence, which I loved and missed. Nothing paranormal about it — just a sense we all get at times.

shielding with tarps whatever needed to stay dry. I kept feeling my father’s presence in a way I often do when I’m fixing stuff around there. He seems to be witnessing my work, approving. Over the course of the day, I was steeped in this feeling of his presence, which I loved and missed. Nothing paranormal about it — just a sense we all get at times.

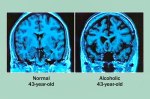

My dad had died 13 years after I got sober in AA. For me, watching his alcoholism progress was especially painful because he did not want what I had. Instead, he continued to believe the same lie he’d told himself for decades, that though he needed to drink less, alcohol was still his best friend. After he was forced to retire at 70, his “start time” for drinking gradually crept into the morning hours — he’d pour wine into his tea cup. His liver and heart enlarged, and his brain shrank, but he dismissed these medical warnings as absurd until he succumbed to alcoholic cardiomyopathy at age 85. That’s not young, I know, but just 15 years prior, he’d been beating his law students in games of squash.

Early Sunday morning at the cabin, I decided to try to reach his spirit. I was alone but for one friend in the second cabin who would, I knew, sleep in late. So I made up my mind: I would seek Dad. I was sitting in what used to be his place at the table, facing the row of windows that fronts the cabin and looks out at Puget Sound.

Early Sunday morning at the cabin, I decided to try to reach his spirit. I was alone but for one friend in the second cabin who would, I knew, sleep in late. So I made up my mind: I would seek Dad. I was sitting in what used to be his place at the table, facing the row of windows that fronts the cabin and looks out at Puget Sound.

I closed my eyes to meditate, focused on the crackle of the fire and my own breathing. I had no more clue than you do how mediums work, so I just tried to call up that feeling of closeness I’d had with Dad the day before. Then I began to inwardly address him. “Dad, please say something to me. I want to hear from you. Please come to me. Please speak to me. I am ready. I am listening. Please.”

Nothing happened. I kept trying. More nothing.

This lack of response seemed to drag on for ages, but in reality it was probably about five minutes. I never lost faith that Dad could hear me. I knew there was some veil separating us, keeping me deaf to him. Then, among the many invitations I’d tried, I framed this particular question: “Is there anything you’d like to tell me?”

WHOOSH!!!

You know when a powerful gust of wind hits you full in the face? That was the experience I had, but energetically. My dad’s presence, his personality, his unique energy as a living man — not just as my father but the whole man he’d been — swept over me. This wasn’t the guy I’d been seeking, the weary, discouraged, beaten-down father I’d known for his last fifteen years. He was young! I didn’t see him, but he filled my awareness with the powerful charisma he’d had during the years I’d loved him most intensely, when I was about five and we read books together and I learned from him to ride a bike and tagged along through all his yard work and snuggled with him on the chaise lounge in the sunshine. This was he! But I also felt his ambition to be, to do, to love! He was powerful.

Next, I became aware he was showing me an image: something white with squares of fine wire mesh. It was the old crib! My parents had used a really weird crib for all four of us kids; instead of bars it had rectangles of bug screen, along with a foldable top that would keep out bugs entirely — though we lived in Seattle with very few bugs. I saw it again at closer range, and then closer still. I realized I was seeing his view of approaching it; I was inside his memory and he knew that his baby — I — was in the crib, though he stopped short of where I might actually see myself. Huge amounts of love radiated from him for that infant, HUGE love, along with tremendous joy and excitement and gratitude that I had entered this world via him. It was a sacred honor to him — then and now — that I had come into my lifetime through his.

Blown away as I was by all this, it took me a few seconds to sense his actual response to my question, the thing he’d broken through the veil to tell me. It was this: “All of you was there then, all of you in that tiny baby — and when I lived, I loved THAT!”

My mind still faltered to understand his meaning, so he added, “You didn’t have to do anything.”

Now I understood. He was right: all my life, he’d pushed me to excel. If I got an A- on anything, he’d pretend to get very grave about it — a joke, but not really a joke. When I decided not to pursue a PhD, when I came out as (temporarily) gay, when I left a tenured teaching post — always I’d encountered his will, however subtle, that I be something more. What needed amendment, what he’d crossed the veil to give me, was the knowledge that always, in his heart, he had loved me without condition and with tremendous rejoicing.

I understood. I sent him my deepest love and told him how grateful I was to be his daughter. But then my skeptical mind butted in: What kind of craziness was this — communicating with my dead dad?! So I asked him directly, “Dad, how do I know this is really you?”

Again, he showed me an image — something I’d never seen in my own life. In the corner of that crib sat a bright pink, brand new Teddy bear. It was downright garish. But a moment later, I recognized it as the old, one-eyed, much-loved, squashed, and faded Teddy bear I’d known in my childhood. “This was the first stuffed animal we got you,” Dad told me, “…and you named him ‘Áha.'”

With that, he was gone.

Amazement filled me. Yes, yes, the name of that Teddy bear was Áha! I’d not thought of it in 45 or years or so, but I remembered! Áha held special meaning for Dad because one of his morning routines for many years was to make my sister’s and my beds, on which he would set up little pageants featuring our carefully posed and balanced stuffed animals with various toys or props. Áha might have on a Halloween mask and be scaring all the other stuffed animals; he might have a little book and be reading to them; he sat with the others at a little table with toy foods. Every day, Dad poured his love for us into these little games. Though I’d much preferred other stuffed toys myself, he’d always given leading roles to Áha. Now I knew why: Áha had been the first.

Dad had was gone — of that I was sure — but the knowings he’d given me  continued to resonate. I was amazed at the succinctness, the iconic concentration, the genius of each message! As a mother, I knew the feeling he was describing — that immense love for one’s baby. I can also remember toys my grown son has long since forgotten. How had Dad picked out an image only he (& Mom) could know — bright pink new Áha sitting in the corner of the crib — and connected it to a name I couldn’t have recalled for a million dollars without his prompting, but knew was right?

continued to resonate. I was amazed at the succinctness, the iconic concentration, the genius of each message! As a mother, I knew the feeling he was describing — that immense love for one’s baby. I can also remember toys my grown son has long since forgotten. How had Dad picked out an image only he (& Mom) could know — bright pink new Áha sitting in the corner of the crib — and connected it to a name I couldn’t have recalled for a million dollars without his prompting, but knew was right?

I’m happy to know my dad has regained all his power on the other side — all his joy and love and vibrancy. Alcoholism burdened him and masked them later in his life, but it’s an illness of the brain, that fatty labyrinth of neurons we use to navigate on Earth. It can’t touch our spirits, which have love as their sole source.

You’d think that, having discovered I have the capability to connect with the dead, for cryin’ out loud, I would find the time to “develop” my mediumship skills. It seems a pretty huge gift, one worth cultivating, even if you’d have to sacrifice other interests to make space — right? But how many things do YOU want to do that you can’t seem to make time for? Earning a living is quite a grind! Keeping the house from getting totally gross and falling apart is a grind! And I LOVE to climb mountains, so staying in shape physically takes a lot of my time. I’ve tried a few other times to reach Dad or my sister or AA friends lost to overdose, but always my head is just too full of clutter and unrecognized fears that block communication.

Maybe I’ll try again at the summer cabin this spring. Until then, here’s a new video of me telling the story of my NDE and some paranormal aftereffects.

[No link? See “JeffMara Podcast” on YouTube or remove spaces from https: //youtu.be/ RXp2jbLWuD0 ]

![]()

but refusing to accept that fact. Denial is, however, a

but refusing to accept that fact. Denial is, however, a  For example, two of my relatives drank hard for over a decade. This couple worked so hard and lived at such a frenetic, globe-trotting pace that they simply could not wind down without cocktails. When staying for a visit, they would put away a gallon of vodka in a matter of days. More than once they announced they were going “on the wagon,” only to be drinking hard again in a few months. They were gradually gaining weight, their faces often flushed and bloated. I suspected alcoholism.

For example, two of my relatives drank hard for over a decade. This couple worked so hard and lived at such a frenetic, globe-trotting pace that they simply could not wind down without cocktails. When staying for a visit, they would put away a gallon of vodka in a matter of days. More than once they announced they were going “on the wagon,” only to be drinking hard again in a few months. They were gradually gaining weight, their faces often flushed and bloated. I suspected alcoholism. by the age of 23. My few friends had cut back on drinking post-college, so I tried to as well — except when I didn’t! Yes, I made resolutions to drink less, not just at New Years but ANY time I was ghastly hungover (i.e. most mornings) — resolutions I was able to stand by for a good 5 hours! After that, a drink began to sound, for the zillionth time, like a good idea. So I “changed my mind” and drank.

by the age of 23. My few friends had cut back on drinking post-college, so I tried to as well — except when I didn’t! Yes, I made resolutions to drink less, not just at New Years but ANY time I was ghastly hungover (i.e. most mornings) — resolutions I was able to stand by for a good 5 hours! After that, a drink began to sound, for the zillionth time, like a good idea. So I “changed my mind” and drank.

I passed without a drink. I felt healthier, had more energy, was cheery at work. But LOVE not drinking? What are, you, nuts? I could hardly wait for the month to be over so I could drink again, because any life without drinking struck me as beyond dull — it would, I knew, be brash, relentless, barren, and joyless. Alcohol, I felt, was the oil in the engine of my life.

I passed without a drink. I felt healthier, had more energy, was cheery at work. But LOVE not drinking? What are, you, nuts? I could hardly wait for the month to be over so I could drink again, because any life without drinking struck me as beyond dull — it would, I knew, be brash, relentless, barren, and joyless. Alcohol, I felt, was the oil in the engine of my life.

and the rest, many newly sober alcoholics can’t silence the part that tells them a drink would make everything better. In my case, god somehow struck that voice with laryngitis about 24 years ago, so the best it can do is a hoarse whisper: A drink would be nice! To me, that suggestion sounds about as believable as Arsenic would be nice! Putting your hand down the sink’s garbage disposal would be nice! Actually, I don’t have a garbage disposal, but if I did, the prospect of drinking would appeal to me about as much.

and the rest, many newly sober alcoholics can’t silence the part that tells them a drink would make everything better. In my case, god somehow struck that voice with laryngitis about 24 years ago, so the best it can do is a hoarse whisper: A drink would be nice! To me, that suggestion sounds about as believable as Arsenic would be nice! Putting your hand down the sink’s garbage disposal would be nice! Actually, I don’t have a garbage disposal, but if I did, the prospect of drinking would appeal to me about as much. I tried super hard to find happiness outside myself. If I could just get with the right people, afford the right stuff, and be seen in the right places, with just the right amount of a buzz or high, I’d clinch it! But all I did was fuck up my life — and others’.

I tried super hard to find happiness outside myself. If I could just get with the right people, afford the right stuff, and be seen in the right places, with just the right amount of a buzz or high, I’d clinch it! But all I did was fuck up my life — and others’.

“The god part” is, without question, the biggest hurdle of the AA program for countless sick and dying alcoholics and addicts. For me it certainly was, because when I read that word “God” coupled with “He” in the 12 steps, I immediately thought of religion, of versions of God as a humanoid king or judge. And that image made me barf. It seemed extremely inconvenient that the only thing AA could offer to save my life was something so hokey as a higher power.

“The god part” is, without question, the biggest hurdle of the AA program for countless sick and dying alcoholics and addicts. For me it certainly was, because when I read that word “God” coupled with “He” in the 12 steps, I immediately thought of religion, of versions of God as a humanoid king or judge. And that image made me barf. It seemed extremely inconvenient that the only thing AA could offer to save my life was something so hokey as a higher power.

My first IANDS meetings in 2012 felt very much like my first AA meetings. Just as in AA I marveled every time a fellow alcoholic articulated experiences I’d assumed to be mine alone, so at every IANDS meeting, I heard bits of “my story” told by others and came to realize I’m just a garden variety NDEr. Many, many NDErs had experienced a “voice” like the one I “hear” — which by that time had saved my life on multiple occasions — and referred to it simply as their guardian angel. One NDEr, upon reviving from death, had been able for a short while to see beings behind the people helping him — beings who were “helping them help me.” For lack of a better word, he said, he calls them angels.

My first IANDS meetings in 2012 felt very much like my first AA meetings. Just as in AA I marveled every time a fellow alcoholic articulated experiences I’d assumed to be mine alone, so at every IANDS meeting, I heard bits of “my story” told by others and came to realize I’m just a garden variety NDEr. Many, many NDErs had experienced a “voice” like the one I “hear” — which by that time had saved my life on multiple occasions — and referred to it simply as their guardian angel. One NDEr, upon reviving from death, had been able for a short while to see beings behind the people helping him — beings who were “helping them help me.” For lack of a better word, he said, he calls them angels.